History

The Dutch East Indiaman Waddinxveen wrecked, together with the Oosterland, during a storm in Table Bay. The ships were stranded by a strong north-westerly gale just four days after the arrival of the Waddinxveen.

The cargo consisted of porcelain, and copper coming from Indonesia, China and Japan, as well as textiles, saltpetre, cloves and pepper. Cannons were also found, and the ship could be identified by these cannons and the VOC emblem.

The wrecking of the Waddinxveen, together with the Oosterland, resulted in a significant setback for the Dutch East India Company as the ships were carrying expensive cargo. Some of the cargo, however, could be saved and was transported back to Patria by the ship Noordgouw (DAS: 5990).

Description

The Waddinxveen was built in 1691 in Rotterdam and belonged to the Enkhuizen Chamber.

| Skipper | Thomas van Willigen |

|---|---|

| People on board | 142 |

| Length | 145 feet (44.2 m) |

| Tonnage | 751 ton (376 last) |

Status

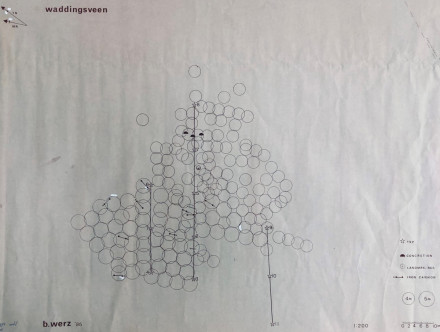

The Waddinxveen, along with the Oosterland, was discovered by divers in the late 1980s and they, together with maritime archaeologist, Bruno Werz, initiated a joint project to research and excavate the remains.

During the excavation of the Oosterland, some of the team members decided to explore an area nearby where they believed another wreck was located. This wreck turned out to be the Waddinxveen. It was decided to include this wreck in the excavation project, although, due to the huge sand overburden and the rate at which the sand moved across the site, less work was undertaken on this wreck.

The results of the work have subsequently been published in various academic reports (e.g. Werz 1999, 2009; Sharfman 1998).

The Waddinxveen was excavated by maritime archaeologist Bruno Werz on behalf of the National Monuments Council and SAHRA. Bruno Werz wrote a book about his research on the wrecks of the Waddinxveen and Oosterland.

Excavators of the wreck note that there is not much structure left of the Waddinxveen as it lies on a small rocky reef and, at the time of wrecking, it would have likely broken up and washed ashore. The wreck lies near the mouth of the Salt River and, as such, the dirty river water makes visibility bad. Additionally, the wreck is generally covered over with a thick layer of sand, sometimes 2 to 3 metres deep. These conditions have prevented extensive excavations of the wreck.

Several salvors and divers showed an interest in the wreck. This resulted in some disagreements and contentions between various factions. Salvage work removed some of the cannons before the site could be excavated.

The recovered artefacts were mainly copper ingots and porcelain and were split between the divers and the museum. There is a large archive of artefacts and documents held by Iziko Museums and Bruno Werz.

The wreck of the Waddinxveen is protected in terms of the National Heritage Resources Act, No. 25 of 1999. This act regards historic shipwrecks as well. The site may not be disturbed without the permission of the South African Resources Agency (SAHRA) and artefacts removed from the wreck may not be traded without SAHRA's permission.

References

- Werz, Bruno E.J.S. (2004).

'Een bedroefd, en beclaaglijck ongeval'. De wrakken van de VOC-schepen Oosterland en Waddinxveen (1697) in de Tafelbaai.

Zutphen, Walburg Pers. - DAS 5973.2.

- Lesa la Grange, Martijn Manders, Briege Williams, John Gribble and Leon Derksen (2024).

Dutch Shipwrecks in South African Waters: A Brief History of Sites, Stores and Archives [Unpublished]. - Dagregister Kaap , 24-5-1697.