History

The wrecksite of the Spanish barque Ulpiano was uncovered as a consequence of coastal erosion in late 2012 and became completely unearthed in early 2013 in close proximity to the Süderoogsand beacon. It was investigated by the ALSH (State Archaeology Department of Schleswig-Holstein), most notably Dr. Hans-Joachim Kühn, who identified the wreck.

Ulpiano was launched in 1870 at the Watson's shipyard in Sunderland, North-East England, for the Spanish businessman Ulpiano de Ondarza (1832-1893) from Mundaka, Spain. It was built in accordance to the newest technical standard, classified as "100A1" in Lloyd's Register. The hull was clad by riveted iron plates covered by a concrete layer to prevent corrosion.

On Christmas Eve 1870 the ship was driven onto the Süderoogsand in a strong gale. All crew members were rescued.

Description

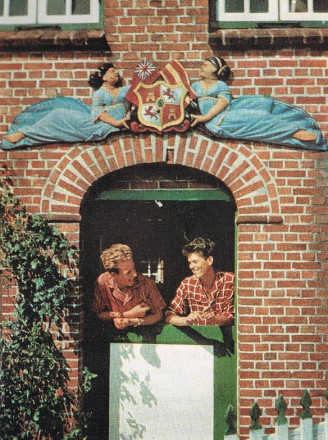

The fate of the Ulpiano was locally known long before its re-discovery, as its stern ornament had been removed from the wreck shortly after the wrecking and adorned the pediment of the shore-bailiff's house ever since. It features the coat-of-arms of Castile and Leon as well as the Spanish flag and the British Red Ensign to indicate the home port and the trade route.

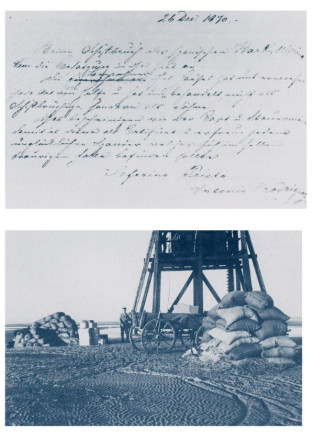

Although Ulpiano is listed in Lloyd's Register of Shipping from 1871 to 1881, her loss for the year 1870 is confirmed by local sources in the district archive and a certifique in private ownership written by captain Seferino Prieto and co-signed by his navigator Antonio Rodriguez on 26.12.1870. The letter confirms their rescue and elaborates that they were not merely treated as castaways, but hosted like sons (Hans-Joachim Kühn, pers. comm.).

The entire crew was rescued by Hallig Süderoog's shore-bailiff Paul Andreas Paulsen. The islanders hosted the crew for 10 weeks, as heavy ice prevented their immediate transfer to the mainland. Some of the cargo was salvaged by cart shortly thereafter, as shown on the photo above.

The location of the wreck suggests that the ship was intentionally set aground in close proximity to the beacon, which contained a save-room for castaways. Hans-Joachim Kühn pointed out that the beacon was not in operation at that time, as all navigation aids were cleared during the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71) for strategical reasons. It is not clear, however, whether the beacon was totally demolished or simply not lighted. The photo above (if concurrent to the letter) would suggest the latter.

| Master | Seferino Prieto |

|---|---|

| People on board | 12 |

| Length | 130 feet (39.6 m) |

| Width | 25 feet (7.6 m) |

| Draft | 15 feet (4.6 m) |

| Beam | 25 feet (7.6 m) |

| Tonnage | 348 ton |

Status

The Süderoogsand is an unhabitated sandbank, which is in continuous movement und partially inundated at high tide. Due to scouring, the wrecksite has become rapidly exposed in the course of 2013. Situated in the surf zone of a high energy tidal environment, the wreck has deteriorated considerably since its discovery, yet remains of the wrecksite are reportedly still visible to this day.

References

- Hansen, K. (2011).

Das Geheimnis der Ulpiano.

Heide: Boyens Buchverlag. - Lloyd's Register Foundation (1871).

Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping.

London, Wyman and Sons. - Hallig Süderoog.

Hallig Süderoog und ihre Geschichte (Hallig Süderoog and its history). - SHZ (news article).

Das Rätsel der „Ulpiano“. - FAZ (news article).

Erosion macht Schiffswracks auf Sandbank sichtbar. - Hamburger Abendblatt (news article).

Als Schiffsleute den Flamenco nach Föhr brachten.