History

In 1939, amateur archaeologist Basil Brown was doing research on the land of Edith Pretty on her request, when they found one of the most amazing archaeological finds in British history: an Anglo-Saxon ship burial.

The Sutton Hoo ship is the biggest and most complete Anglo-Saxon ship ever found, and is longer than many of the largest modern ocean-going yachts. Ships were very important to the Anglo-Saxons. Rivers and the sea were key to communication and travel.

In many ways, it was easier to travel by water than by land in that period, so people in Denmark and the Netherlands would have been the Anglo-Saxons' close neighbors. Recent DNA research has confirmed that Anglo-Saxon immigrants in England were genetically very similar to modern Dutch and Danish people (see Current Archaeology vol. 312).

Ship burials

A ship burial is a burial in which a ship is used as a container for the dead and the grave goods. This style of burial was seen as a way for the dead to sail to Walhalla. A ship burial was a high honour and only for the richest classes.

This ship burial is part of an Anglo-Saxon royal burial site with 18 mounds dated to 600-650 AD near Sutton Hoo, Woodbridge, Suffolk. Sutton Hoo belonged to the kingdom of East Anglia in the 7th century.

The ship had probably been sailed upriver and then dragged overland to a pit dug at the burial spot. The ship was then covered with a large mound of soil.

The grave is one of the most magnificent archaeological finds in England. It provides a good picture of the early medieval period in Northern Europe.

King Rædwald

The magnificence of the ritual and possessions, the far-reaching connection which they demonstrate, and the inclusion of objects denoting the personal authority of the individual buried there, definitely point to a person of the very exceptional status. King Rædwald is a likely – but not the only - candidate.

Rædwald, son of Tytila, was king of East Anglia from ca. 599 until 624 AD. He was probably baptised around 600 by Augustine of Canterbury. Yet in his temple there were two altars, one dedicated to Christ, and one for to the Anglo-Saxon gods.

In 616 AD he waged a war against Aethelfrid of Northumbria. During the battle of the River Idle, Rædwald's son died and Rædwald killed Aethelfrid in combat. Because of this action, Rædwald's authority became sufficiently universal for Bede to recognise him as the most important king in Britain. Bede called him Rex Anglorum, 'King of the English'.

Description

This Anglo-Saxon longboat was reused as a ship burial. Technically and as far as the dating goes, the Sutton Hoo ship can be placed between the Nydam ship (300-400 AD) and the Viking longboats of the 10th century. It seems to have been an open rowing vessel with 20 oarsmen on either side. There is no evidence of a sailing tackle. But as the mast would be amidships where the burial chamber was, there is no negative or positive proof if it was a sailing vessel.

Coins give a terminus post quem of ca. 625 AD of the ship burial. Several repair strips on the hull prove that the ship was in use for a considerable time before it was used at the burial site. The construction of the ship is dated to 600-610 AD.

Construction

The hull seems symmetrical and was clinker built with nine strakes on either side of the keel board including a gunwale strake. The planks are tapered towards the bow and the stern. The strakes were constructed from several lengths of planking which were joined together by rivets. No wood survived but surviving wood grain on the rivets shanks suggests oak.

There is no trace of a meginhúfr, a development seen in Viking ships where the waterline plank is thickened and strengthened. 26 wooden frames strengthened the form from within, which were more numerous near the stern where a steering-oar might have been attached.

| Length | 88 ½ feet (27 m) |

|---|---|

| Width | 14 ½ feet (4.4 m) |

Status

Location

The ship burial (Mound 1) is part of a part of an Anglo-Saxon burial site from the 7th century near Sutton Hoo, Suffolk.

Excavations

In 1939 Basil Brown excavated Mound 1 which was the largest of 18 burial mounds at Sutton Hoo. He discovered an intact ship burial. When the importance of the find became clear, a team of archaeologists from the British Museum took over. Most of the artefacts found during the subsequent excavations went to its collection.

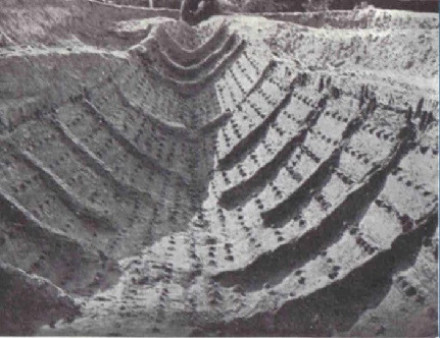

Although practically none of the original timber survived, the excavation of the ship in Mound 1 presented a very perfect image of the vessel. Discolorations in the sand had replaced the wood but had preserved many details of the construction, and nearly all of the iron planking rivets remained in their original places. Hence it was possible to survey and describe what was merely a ghost of the original ship. Asides from the amazing image of the ship, many rare artefacts from the Anglo-Saxon period were found, that were put into the mound as grave gifts.

A re-excavation was performed between 1965 and 1967, providing technical details and better drawings of the ship. Between 1967 and 1970 the soil dump from the excavation 1939 was excavated. In this, lots of lots of small finds were made.

References

- Article Anglo Saxon DNA research.

- Rædwald of East Anglia.

- Konige der Nordsee 250-850 , red. E. Kramer et al, Den Haag 1999.

- Editor (2016).

Warhola, B.,1998: Italian Frogmen Attack Austrian Dreadnought, Old News Vol 9, No 5Ed.

Current Archaeology, vol. 312.

pp 6. - British Museum.

Anglo Saxon ship burial at Sutton Hoo.