History

The 'Nossa Senhora do Cabo' was a former Dutch ship of the line. The warship 'Gelderland' was built in 1711 at the Admiralty shipyard in Amsterdam. At that time, the Dutch Republic was still involved in the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) against France.

Sold

After the War of the Spanish Succession, the Dutch navy was reduced in size due to economic circumstances, political divisions, and the diminishing external threat. In June 1717, the Gelderland was sold to Portugal and renamed 'Nossa Senhora do Cabo e S. Pedro de Alcântara'.¹

The ship was converted in Portugal into an East Indiaman. This meant, among other things, that a large portion of the 72 guns on board were removed to create space for additional provisions and cargo.

The ship then departed Lisbon on April 13, 1720, bound for Goa, the capital of Portuguese India. It arrived there on September 9, 1720.

Return voyage

The return voyage to Portugal began on January 25, 1721. On board were, among others, the outgoing Viceroy of Goa, Luis Carlos Inácio Xavier de Meneses (Conde da Ericeira), and the Archbishop of Goa, Sebastião de Andrade Pessanha. The cargo consisted of silk, spices, Chinese porcelain, diamonds, precious stones, gold, and books. There were 130 crew members, several passengers, and slaves on board. Of the original 72 cannons, 30 were still mounted. (Mercure, 54)

Storm

On March 9, the ship encountered a prolonged storm. To keep the ship afloat, (nine) guns, weapons, and cargo were thrown overboard. When the storm subsided on March 13, the ship had lost its masts, the rudder was split, and the stern was damaged. Despite this damage, the ship reached Saint Denis on the Isle of Bourbon on April 4. The passengers and crew were landed, and repairs began. During these repairs, two ships approached the roadstead on April 26.

Captured

These turned out to be two pirate ships. They immediately launched an attack:

"The Victory, one of the pirate ships, equipped with 36 guns and 200 men, commanded by La Bousse, anchored under her bowsprit, and at the same time the other pirate, named The Fancy, commanded by Edward England, arrived on the starboard side with 38 guns and 280 men." (Mercure, 61)

The men on board soon surrendered. But the brave Count D'Ericeira continued fighting on the quarterdeck until his sword broke.*

The pirates took the ship in triumph to Saint Paul, a bay further on. On board was the largest booty ever found by pirates in a single ship. The Nossa Senhora was repaired as best they could. The pirates renamed her "Victory" and then disappeared, according to the officially released story in the media of the time (Mercure, May 1722).

The story of Bucquoy

The ultimate fate of the Victory, ex-Gelderland, ex-Nossa Senhora do Cabo, is not found here, but in other sources: the eyewitness Jacob De Bucquoy. He was a surveyor employed by the VOC and was captured by the pirates.

In 1721, the Dutch East India Company had just begun building a fort in Delgoa Bay in Mozambique. It was far from finished when, on April 19, 1722, three ships sailed into the roadstead. They turned out to be the same pirates. Jacob Bucquoy describes what happened.

The illustration from Bucquoy's book shows the moment of the attack on the VOC fort. We see the two large ships and the small brigantine. In the gunpowder smoke of the middle ship, we see the hooker De Kaap.

The pirates arrived on two large ships and a brigantine and anchored just outside the fort under construction. A small ship, a "hoeker," lay in front of the fort. After a brief exchange of fire, the fort surrendered. The pirates came ashore: debauchery and rudeness were the order of the day… insulting women, public drunkenness, and then inflicting violence on the natives… (Bucquoy 28-31)

The pirates camped at the fort for two months. On June 30, 1722, they departed. The departing fleet consisted of the Victory, Defense, the brigantine, and the Dutch "hoeker." Several Dutchmen, including Jacob Bucquoy, were taken on board. (Bucquoy 37)

Storm and Separation

After departure, the fleet encountered a heavy storm, during which the brigantine was lost and the large ship was damaged again. Pirate captains Taylor and Labouse had a falling out. Labouse was deposed as captain. This led to the pirates splitting up: Labouse received the damaged large ship, Taylor took over Defense, and the hooker was left to the Scottish pirate Elck. (Bocquoy, 58)

End of the Victory

Bucquoy and his group of 22 were put ashore in Madagascar, and the pirates disappeared. After eight months alone in the wilderness, a small boat with survivors from 'Victory' joined them in the bay. They reported that the large ship had run aground and broken up on the Noordhoek (Cap d'Amber) of Madagascar. That was the inglorious end of the Nossa Senhora do Cabo (Nossa Senhora do Cabo). (Bocquoy, 86)

There is another version of the fate of the Victory, and it is found in Charles Johnson's famous book History of the Pyrates,(1724) which says that the Victory was in Madagascar with Captain Taylor when:

The Refidue having therefore no Occafioa for two Ships, the Victory being leaky, she was burnt, the Men (as many as would) coming into the Caffandra under the Command of Taylor (Johnson, 136)

The treasure of Levasseur

A whole series of legends arose after Olivier Levasseur's death. He supposedly buried the enormous treasure of Our Lady of the Cape in a secret location. He had written down the instructions in cryptogram style on a scroll of parchment. Just before his execution, he allegedly threw it into the crowd with the words: "Find my treasure, whoever can understand it!" (Mes trésors à qui saura comprendre). In 1934, French historian Charles de La Roncière published a book in which he claimed to have found the parchment in question in the French archives.²

Although the capture of the Nossa Senhora in 1721 by pirates, including Olivier Levasseur, did indeed take place, despite numerous searches and investigations, no concrete evidence of the existence of any treasure was ever found.

Jacob de Bucquoy eventually returned to Amsterdam as the sole survivor after many wanderings. He published a booklet in which he chronicled his adventures.

Captain Taylor was later granted amnesty in Panama in exchange for his ship and 121 chests of gold.

Captain Levasseur was discovered years later by chance on an islet in the Bay of Antongil. He was arrested and hanged on the beach at Saint Denis in July 1730. His body was then thrown into the sea.

Description

Built: Amsterdam, Admiralty Shipyard, 1710-1711. Shipbuilder: Jan van Rheenen.

Owners: Amsterdam Admiralty (1711-1717); Portuguese Navy (1717-1721)

Captain: Francisco de Moura (1717-1721), John Taylor (1721-1722), and Olivier Levasseur (1722-1723)

| Master | Francisco de Moura |

|---|

Status

Archaeology 1999 - 2015

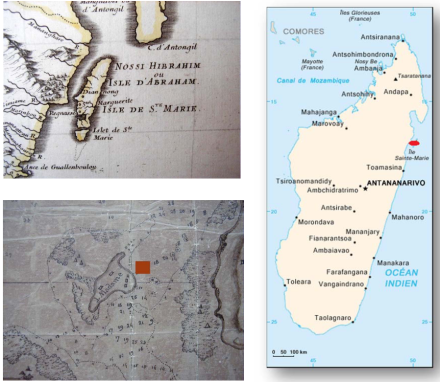

Recently, an article was published by two maritime archaeologists (Brandon A. Clifford and Mark R. Agostini van de particuliere organisatie Historic Shipwreck Preservation,** ) stating that the wreck of the Nossa Senhora do Cabo could have been found near the island of Nosy Boraha in Madagascar.³

This was once the famous pirate harbor of Saint Marie, inhabited by pirates between approximately 1690 and 1720. Afterward, it was virtually abandoned. Several ships were sunk by pirates in the approach to the harbor. According to the archaeologists, one of these is the Nossa Senhora. Based on Johnson history of pyrates 1724:

The Refidue having therefore no Occafioa for two Ships, the Victory being leaky, she was burnt, the Men (as many as would) coming into the Caffandra under the Command of Taylor (Johnson, 136)

More than 3,000 objects have been found, some of which correspond to the period.

The four locations are very close together, so many of the finds could originate from multiple wrecks. There is talk of parts of ship structures that suggest a Portuguese construction method. Dendrological research could quickly provide clarity in this matter. The Nossa Senhora do Cabo was originally built in Amsterdam.

Madagascar. Ile Sainte‐Marie. Maps drawn by French engineers. Top left by the Sieur Sanson drawn in 1667; bottom left in 1818, indicating the wreck area. Right ‐ general map of Madagascar.

UNESCO research

Madagascar is a signatory to the UNESCO 2001 Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage. In 2015, a UNESCO research team carried out an evaluation study on the site. One of the conclusions was that the locations are very close together and the origin of many of the finds cannot be traced back to a single wreck.

As a conclusion it can be said, that several historic wrecks are indeed lying in the bays of Sainte Marie Island. They are reasonably preserved and their extensive research would be of considerable archaeological interest.

For any further research it is however recommended to follow closely the regulations of the Annex of the UNESCO 2001 Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, as ratified by Madagascar, and to only permit interventions by a competent team under the lead of a qualified

underwater archaeologist and under a strict control by the authorities.

Recommendations

1. Further archaeological investigations and historical background research on the area off Sainte‐Marie are recommended. The area was subject to heavy ship traffic for centuries, and the large volume of wrecks in the area requires a broad multi‐disciplinary approach to inventory and research the highly significant and scientifically important wrecks;

2. For any further works on the sites located in Sainte‐Marie it is strongly recommended to insist on the submission of an accurate and comprehensive project design in line with the 2001 UNESCO Convention, and to insist on the qualifications of the team proposed and to make sure intrusive interventions on any shipwreck site have a scientific goal and do not only serve media interests;

(Scientific and Technical Advisory Body to Madagascar UCH/16/7.STAB/4 p 30,31)

Click here for the STAB rapport

(**) From 1999 until 2015 a team led by Mr Barry Clifford came to Madagascar to explore the pirate wreck sites off the island of Sainte Marie. The exploration was authorized by the Government of Madagascar, specifically the Ministry of Culture in 2012. A concessionary contract was signed

December 2012 for the exploration and salvage of wrecks. The concession foresaw a 50/50 division of the finds between the Government of Madagascar and Mr Clifford. Furthermore the contract foresaw training for the underwater archaeologists of Madagascar and the restoration of the museum in Îlot Madame

References

- G. Conceição Silva.

Un curioso documento do Sec. XVIII. - Mercure de France, may 1722.

Relacion du voyage de son excellence M. le comte d'Enriceira, grand de Portugal. - Bucquoy, Jacob de.

Zestien jaarige reize naa de Indiën. - Brandon A. Clifford and Mark R. Agostini PhD.

From Goa to Sainte-Marie: An Archaeological Case for the Identification of the Nossa Senhora do Cabo. - Michel L’Hour.

16-24 June 2015 mission of the Scientific and Technical Advisory Body to Madagascar: report and evaluation. - Charles Johnson (1724).

A general history of the pyrates, : from their first rise and settlement in the Island of Providence, to the present time.

pp 134 e.v.