History

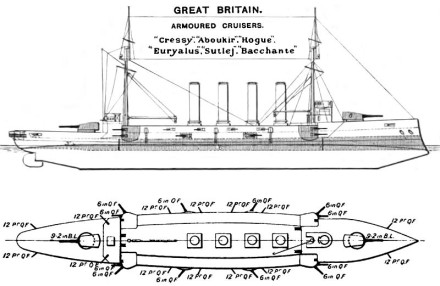

HMS Aboukir was a Cressy-class armoured cruiser, a class which consisted of five other ships. The design of the Cressy class incorporated heavy armour and a pair of 9.2-inch guns that served to address the criticisms that had been made against the previous Diadem class. Until 1908, Aboukir and her sister ships served in home waters, the Mediterranean and the Far East, at which point they were called home and put on reserves.

At the beginning of World War I, the Cressy-class cruisers were already obsolete but put on active duty nonetheless. Five Cressy-class cruisers formed the Seventh Cruiser Squadron, prophetically nicknamed the ‘live bait squadron’ due to the obsolescence of the ships and the fact that they were crewed mainly by inexperienced reservists.

In the first months of the war, the area of the North Sea known as the ‘Broad Fourteens’ was being patrolled by Cruiser Force C, made up of the Cressy-class Seventh Cruiser Squadron. Many senior naval officers were opposed to this patrol, as they felt that the ships were vulnerable to German attack. On 20 September 1914, the force prepared for patrol under Rear Admiral Christian, who had taken over from an absent Rear Admiral Campbell, who usually had command of the force. The weather was too bad for the cruisers to be accompanied by destroyers, and, due to damage and a lack of coal on his ship, Rear Admiral Christian was forced to stay behind as well. Command of HMS Cressy, HMS Hogue and HMS Aboukir was given to the captain of Aboukir, Captain Drummond. The three cruisers set out on what was to be their final patrol, as, two days later, disaster struck.

Action of 22 September 1914

Early on the morning of 22 September 1914, the three cruisers of Cruiser Force C, HMS Cressy, HMS Aboukir and HMS Hogue were patrolling near the Netherlands in the North Sea, when they were spotted by the German submarine U9, under command of Otto Weddigen. The ships were sailing at a speed of 10 knots, in a straight line, which went against common naval orders of maintaining a speed of 13 knots while moving in a zig-zag pattern to avoid enemy attack. Unfortunately, the Cressy-class cruisers could not maintain such a speed and it was common at the time for naval commanders to disregard the order to move in a zig-zag pattern. At 6:25 in the morning, U9 fired a single torpedo at Aboukir and struck her port side. Aboukir flooded quickly, and despite counter-flooding measures, began to list severely to one side. As his ship lost power and thinking that she had struck a mine, Captain Drummond ordered his crew to abandon ship and ordered Cressy and Hogue to close and assist. As sailors began to jump in the water, since only one boat had survived, Drummond realized that the ships under his command were actually under attack, and ordered them away, but it was too late.

As Aboukir rolled over and sank, about half an hour after she was first hit, Hogue circled around her to pick up survivors. U9 fired two torpedoes, hitting Hogue amidships, which flooded the engine room, and caused her to sink within 10 minutes. After hitting Hogue, U9 fired two torpedoes at Cressy – one missed, but the other struck her side, rupturing several boilers in the process, which scalded the men present in the compartment. Cressy sank within 15 minutes.

The whole action took less than 2 hours, and by the time the German submarine left the scene, 1459 sailors were dead and only 837 were subsequently rescued. An official inquiry into the disaster was launched, and it was determined that fault for the incident lay with all the senior officers involved. Captain Drummond did not move his ships in the ordered zig-zag pattern and did not call the destroyers that should have accompanied the three cruisers out to sea when the weather had sufficiently cleared. He stated that he was not aware that he had the authority to do so, thus fault lay also with Rear Admiral Christian for not making the full authority of his command clear. Rear Admiral Campbell was at fault, as he was not present at all, and showed very poor performance at the inquiry, where he stated that he was not aware of the purpose of his command. Finally, fault was determined to lie with the Admiralty in general, for continuing such a dangerous patrol against the advice of senior sea-going officers.

Description

The Aboukir was a Cressy-class armoured cruiser built in the Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering Co Ltd, Govan, Scotland. She was laid down in November 1898, launched in May 1900 and completed in 1902. She had steam propulsion and a complement of 725-760. Her armament consisted of 29 guns and two torpedo tubes.

| Master | Drummond |

|---|---|

| Speed | 21 knots ~ 24 mph (39 km/h) |

| Length | 472 ½ feet (144 m) |

| Draft | 26 feet (7.9 m) |

| Beam | 69 ½ feet (21.2 m) |

| Displacement | 12000 ton |

Status

The legal status of the wreck sites of HMS Cressy, HMS Aboukir and HMS Hogue has been in question over the past years. While the wrecks lie off the Dutch coast, they are technically outside territorial waters. The ownership of the wrecks is also in question. As warships that belonged to the British Royal Navy when they sunk, the wrecks would still technically belong to the British government, however, evidence has surfaced that suggests that the wrecks were sold to a salvaging company in the mid-20th century.

After a few recent illegal salvage attempts, there has been a public outcry over the state of the wrecks. Many people are advocating for the official protection of the wrecks as war graves from World War I.

References

- Wikipedia article on HMS Aboukir.

- Henk van der Linden (2012).

The Live Bait Squadron: Three mass graves off the Dutch coast, 22 September 1914.

AbeBooks. - Duik de Noordzee schoon.

The Live Bait Squadron Trailer OUD - YouTube.