Description

The historic roadstead encompasses the entirety of Oranje Bay, St. Eustatius. In the 18th century, thousands of ships dropped anchor here in order to trade at this free port. The roadstead, or road for short, was by far the busiest area in St. Eustatius’ surrounding waters, where the vast majority of ships destined for the island dropped anchor. Nearly all movements of goods and people between ships and the island took place on the road, making it a very important part of the maritime cultural landscape. As trading activities on the island increased, so did the number of ships. According to Lieutenant Cornelius De Jong, who travelled through the Caribbean on the Dutch man-of-war Mars, there were nearly 200 ships at anchor on the road when he first visited the island in September 1780 (De Jong 1807: 96). A few months later, Admiral George Brydges Rodney noted 130 ships on the road (Enthoven 2012: 241). Research into the extent and location of the roadstead was first conducted in the 1980s by the College of Mary & William. Later in 2015, an in-depth documentary and archaeological analysis of the road was conducted by the St. Eustatius Center for Archaeological Research.

Historical artwork provides many clues about the location and extent of the anchorage. Numerous 18th- and 19th-century historical drawings and watercolours of Statia’s road exist, spread across private collections and archives all over the world. These show that some ships anchored close to shore, but most dropped anchor further away from the island. From historical artwork, it can be deduced that the road covered a large area on the island’s leeward side. This is not surprising given the fact that there could be as many as 200 ships on the road.

It seems reasonable to assume – as researchers did in the 1980s – that artifacts on the sea floor reflect the actions of sailors discarding them. In other words, the more artifacts present at a certain location, the more artifacts were thrown overboard, and thus the more ships anchored there. This theory, however, is based on the principle that the current distribution of archaeological material is similar to that in the past. The sea floor in this area – and in many other places around the island – was found to be extremely dynamic. The depth of certain areas can thus change several metres after a hurricane due to large amounts of sediment being moved. It is not only sand that is moved; small artifacts are moved around relatively easily as well. This results in artifacts and other types of heavy sediment being eroded and deposited in particular areas or depth ranges. The distribution of artifacts on the sea floor is therefore much more the result of natural erosion and sedimentation processes than it is a reflection of the location and size of the main historic anchorage area as indicated by past human activities. Even though artefacts were undoubtedly thrown overboard by sailors, given the above, it is likely that many artefacts found in the area that was designated as the main anchorage zone in the 1980s were not discarded by sailors at all; they may have been discarded by people on shore and moved to deeper waters by wave action. The nature of the landing on Lower Town’s beaches, as described above, also contributed to artefacts ending up in the sea.

The maximum depth of the area designated by the researchers in the 1980s as the main historic anchorage, at 900 metres from the shore, is 20 metres or 11 fathoms. Contradictory to this conclusion, the documentary record contains many accounts indicating that a large part of Statia’s anchorage was located further offshore in deeper waters, and was thus much larger than previously thought. The distribution of lost anchors corroborates the findings from the documentary record. Many anchors were found at the anchoring depths described in ship logs, on maps, and in traveller’s accounts.

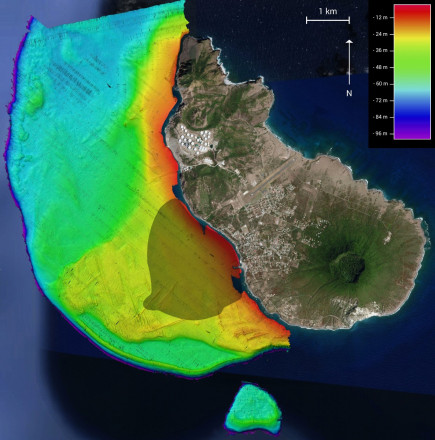

It is, however, too simplistic to use anchor distribution as the only variable in determining the size of the road. Another important variable is the composition of the sea floor, which was a determining factor in deciding where to anchor. The composition of the sea floor was found to be sandy around most anomalies that were investigated, indicating that good anchoring grounds existed around the coral reefs and rocky outcrops that anchors got hooked on. This information, combined with the anchor distribution and documentary evidence – such as anchoring depths – was used to determine the extent of the road. The total area of the anchorage zone was approximately 4.2 square kilometres. It measured 2.5 kilometres at its widest points on a northwest-southeast axis. The westernmost tip was 2.5 kilometres from shore. Taking into consideration that there could be up to 200 ships in port during Statia’s economic boom, this area would have been of sufficient size to accommodate all these vessels. Several anchors were found in locations other than the road, such as Corre Corre Bay and Jenkins Bay. These remote bays, out of sight from town, were ideal for carrying out smuggling activities at times when the colonial administration tried to curtail these practices.

The anchor is the most numerous type of artifact found during the survey of the road. One important issue that warrants discussion is how and why anchors ended up in their present locations. The documentary record holds some answers to these questions. Several 18th- and 19th-century visitors noted that Statia’s road was dangerous during hurricane season, as it was too exposed (Dieterich 1798: 272; Teenstra 1837: 324). The sudden appearance of strong gusts of wind may have caused ships to drag their anchors, causing them to be buried deeper into the sea floor. In this situation, weighing the anchor would have been a lengthy, if not impossible task. The quickest way to start moving was to simply cut the anchor cable and sail away. Another reason why many anchors were lost was because of the underwater topography, which exhibits many reefs containing cracks in which anchors could easily get stuck. Sometimes, when the anchor was being dragged, it would encounter such a reef. Once stuck, it could be very difficult to free an anchor, particularly during strong winds and storms. A rocky composition of the sea floor could cause ships to lose an anchor as well. Not just environmental conditions played a role in losing an anchor, sometimes this was caused by human errors as well. In 1761, Captain Bylandt described an unfortunate situation in the log of the Dutch warship Maarssen (National Archives The Hague 1.01.47.17 – 48, folio 81). The Maarssen had planned to depart St. Eustatius with a number of other ships and sail back to Europe in convoy. As several ships weighed their anchors simultaneously, one ship came too close to the Maarssen and almost crashed into her. To prevent a crash, the Maarssen needed to move away so Captain Bylandt ordered more rope to be added to his anchor. The extra movement this generated to his ship caused its anchor to become detached from the sea floor and the Maarssen to crash into the bow of another ship that lay just downwind from her. In order to become detached, the other ship had to cut its anchor rope, thereby losing an anchor.

During the peak in commercial activities for St. Eustatius in the 18th century, tens of thousands of people were living their lives on Statia’s road, some only for a few days, others for months on end. This entailed living in close quarters for extended periods of time, causing some sailors to develop a short fuse. Accounts of sailors attacking each other or committing suicide or being jailed for misbehaving are some instances of the mental challenges inherent to life aboard a ship which proved too much for some sailors. More activities occurred while these sailors stayed on the road, including loading and offloading goods and ballast which could also take a considerable amount of time. On slave ships, the slave quarters and slave kitchen inside the ship needed to be disassembled when all enslaved people were offloaded. Enslaved people were not always immediately sold or taken ashore, requiring their further care by sailors.

Some regulations influenced the archaeological record as well. No vessels on the road were allowed to throw ballast or any other sinking object overboard. Instead, these had to be offloaded and deposited at a location determined by the harbourmaster (Curaçao Archives, Gouvernement van het Eilandgebied St. Eustatius, Inv. Nr. 248, art. 12). Sailors undoubtedly discarded objects into the sea, particularly on ships anchored further offshore. Nevertheless, this rule may have curtailed these practices a bit, causing fewer artefacts on the bottom of the sea and more in designated dumping areas on land.

By combining archaeological and historical data, it has been possible to produce a precise map of the historical anchorage zone or roadstead, which was found to be much larger than previously thought (see image below). Its large size was necessitated by the fact that hundreds of ships could be at anchor here simultaneously. Anchors themselves are a reflection of the size and locations of historical anchorages, but due to several factors, their use in studying trading activities is problematic at best. They do indicate that ships not only anchored on the roadstead but also in remote bays such as Corre Corre Bay and Jenkins Bay, most likely to partake in smuggling activities.

References

- Johann Christian Dieterich (1789).

Herrn Bergt und Euphrasens Reise nach der Schwedisch-Westindischen Insel St. Barthelemi, und den Inseln St. Eustache und St. Christoph. - Cornelius de Jong (1807).

Reize naar de Caribische Eilanden, in de Jaren 1780 en 1781.

Haarlem, François Bohn. - Marten Douwes Teenstra (1837).

De Nederlandsche West-Indische eilanden in derzelver tegenwoordigen toestand.

Amsterdam, C.G. Sulpke. - Victor Enthoven (2012).

“That Abominable Nest of Pirates”: St. Eustatius and the North Americans, 1680-1780.

Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. (10), number 2. - Ruud Stelten (2019).

From Golden Rock to Historic Gem: A Historical Archaeological Analysis of the Maritime Cultural Landscape of St. Eustatius Dutch Caribbean.

Leiden: Sidestone Press.