History

This wreck was discovered in 1996 during a survey by the regional society for underwater archaeology on the south-west coast of the island of Hiddensee. The use of double-clenched nails as lapstrake plank-to-plank fasteners (typical for Bremen-type wrecks, commonly associated with "cogs") as well as a medieval find-scatter in the vicinity led the responsible archaeologist Dr. Thomas Förster to believe this was indeed a medieval wreck. His assumption was corroborated by a dendrochronological analysis, pointing to a felling date to around/after 1378.

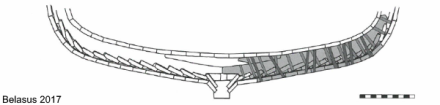

This was one of two wrecks associated with the illusive "Baltic cog type", a hypothesis based on iconographic evidence from ship-depictions on town seals. It differed in that it was a fully lapstrake-built vessel with a beam-keel, thereby deviating from some of the criteria set up for the Bremen-type or bottom-based tradition, which has been commonly associated with cogs. Moreover, instead of the more common oak, this vessel was entirely built of coniferous wood.

The ship-timbers were revisited ex situ within the framework of Mike Belasus' PhD project, who commissioned a new dendrochronological analysis, carried out by Dr. Aoife Daly. This time 12 samples were taken. Surprisingly, the new analysis yielded a strikingly different result: The timber was felled 1804 or shortly thereafter. Based on the master chronologies for pine, the timber originated in south-west Finland.

Description

The wreck has been noted for its second layer of flush-laid (carvel) planks covering the first layer of lapstrake planks.

This style of construction was noted throughout the Baltic Sea region since the mid 16th century, with corresponding finds from Estonia, Poland, Sweden and Russia.

Both, the construction and the choice of coniferous wood as building timber are regarded as indicators for small-scale coastal shipping in rural regions.

Status

The ship-timbers are in a waterlogged storage. The legacy of this wreck's research history highlights that hypotheses on historical type-names can easily crumble when key assumptions about a find are refuted by hard scientific evidence. The archetype of a "Baltic cog" has already become ingrained in popular culture through the initial over-interpretation of this wreck-find.

In fact, the Gellen wreck was presented as "Gellen Cog" (Gellen-Kogge) in the German pavilion at the World Exhibition "Expo 2000", described as an outstanding ambassador for Germany by high ranking officials. It turns out that this credit has to go to Finland instead!

References

- Belasus, M. (2014).

Tradition und Wandel im neuzeitlichen Klinkerschiffbau der Ostsee am Beispiel der Schiffsfunde Poel 11 und Hiddensee 12 aus Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (= Dissertation).

Universität Rostock. - Belasus, M. (2017).

Connecting maritime landscapes or early modern news from two former 'Baltic Cogs' (Mecklenburg-West Pomerania, Germany).

Ships And Maritime Landscapes (= Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Symposium on Boat and Ship Archaeology, Amsterdam 2012).

pp 179-184. - Daly, A. & Belasus, M. (2016).

The Dating of Poel 11 and Hiddensee 12, Mecklenburg-West Pomerania, Germany.

The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 45.1.

pp 170–205. - Förster, T. (2009).

Große Handelsschiffe des Spätmittelalters. Untersuchungen an zwei Wrackfunden des 14 Jahrhunderts vor der Insel Hiddensee und der Insel Poel (= Schriften des Deutschen Schiffahrtsmuseums 67).

Bremerhaven. - Lüth, F., Förster, T. (1999).

Schiff, Wrack, ’Baltische Kogge’.

Archäologie in Deutschland 4.

pp 8–13. - Die Welt.

Expo: Mittelalterliche Kogge getauft. - Der Spiegel.

Ostseewracks neu datiert: Berühmte Schiffe sind offenbar jünger als vermutet.