History

Fort Bay has seen extensive use by humans from Archaic-age Amerindians (1,300BC – 500BC) all the way to the present day. Fort Bay provided several advantages to other locations on Saba for human settlement. Its location to the lee of prevailing eastern currents, along with nearby Ladder Bay, created a large eddy where fine sediments could be deposited offshore. This provided a deep, sandy seafloor, which provided a base for sea grasses, which in turn made habitat for the Queen Conch (Strombus gigas), and one of the best anchorage points on Saba during the colonial period. The queen conch was a valuable food and tool resource for Archaic and Ceramic-age Amerindians, who used conch shells to fashion a variety of tools, including axes, adzes, scrapers, cups, and awls. The nearby Archaic age site, beneath the new diesel electricity plant, features large deposits of tools fashioned from queen conch shells (Espersen 2014). A freshwater spring can be found onshore just west of the present-day small pier, which was exploited from the Archaic period up to the 21st century. It has since been partially buried by coastal erosion deposits following hurricane Maria in September 2017.

The name “Fort Bay” derives from the presence of a small fort that was constructed in the vicinity of the bay, either upon the southern slope of the aptly named “Fort Hill” adjacent and east of the main road that leads to The Bottom, or perhaps upon the southern slope of Bunker Hill. Johannes Hartog (1975:18) claims that this fort was destroyed by a landslide in 1651, but unfortunately he does not reference any of his work throughout his “History of Saba”. A fort kept reappearing on maps of Saba right up to 1816, but it was confirmed the Island Secretary of St. Eustatius in 1773 and later by Governor Edward Beaks Sr. in 1817 that no fort existed on the island by these times (DNAr 1.05.01.02 #629:2/2/1773; BNAr, CO 700/WestIndies33; DNAr 1.05.13.01 #319). The fort at Fort Bay would have been strategically placed as a means to defend the anchorage at Fort Bay, and a nearby settlement at Tent Bay.

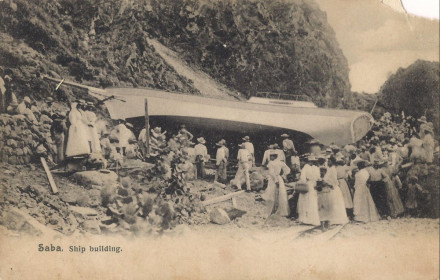

Larger sailing vessels calling into Saba would drop anchor usually at Fort Bay or Ladder Bay, and be serviced from shore by Sabans via locally-made rowboats that would ferry goods and people between them. These boats were also used for fishing around the island. Both fishing and ferry boats were kept on shore at Fort Bay. Some shipbuilding took place on Saba, and larger vessels were built on site, usually at Fort Bay. These were made using locally-available wood, most often the "White Cedar" (Tabebuia heterophylla), though the tree is not actually a cedar. The photo shown below was taken at Fort Bay in the early 20th century, showing a recently finished ship. A completed boat or ship was a grand affair on Saba and attracted many people to witness its launch.

The shoreline of Fort Bay is exposed to extensive erosion from the hillsides above. Efforts to expand Fort Bay and make it safer from erosion began in the 1950's, and included removing entire hillsides. The hill in the background to the right in the photo shown above has since been completely flattened. Construction starting in the 1970’s destroyed any remains of previous structures.

Status

During an underwater survey of the harbour area in 2019 by Ruud Stelten, an anchor was located at a depth of around 10m. It measures 84cm long, 43cm across at the arm, with bills 77cm wide. It originally had a wooden stock therefore it dates prior to the early nineteenth century (Stelten 2019). This is one of many anchors found around the island; one veteran diver living on Saba estimates there are as many as 130, mostly concentrated in the anchorage zones. Saba was considered a “poor island” in the region from the 18th to mid-20 centuries (Espersen 2017, 2018), and as a consequence it received very few calls from merchant vessels. Therefore, the high number of anchors relative to the ship traffic to the island attests to the poor quality of anchorage on Saba.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

BNAr = British National Archives

DNAr = Dutch National Archives

REFERENCES

Espersen, Ryan (2018). From Hell’s Gate to the Promised Land: Perspectives of poverty on Saba, Dutch Caribbean, 1780 to mid-20th century. Historical Archaeology 53(2):773-797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41636-018-0147-2.

Espersen, Ryan (2017). “Better Than We”: Landscapes and materialities of race, class, and gender in pre-emancipation colonial Saba, Dutch Caribbean. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Leiden University, Leiden.

Espersen, Ryan (2014). The Fort Rut Ridge Site: An Archaeological Survey and Limited Excavations. Unpublished site report, Saba Archaeological Center, Saba.

Hartog, Johannes (1975). History of Saba. Van Guilder, Assen.

Stelten, Ruud (2019). An Archaeological Assessment of the Saba Harbour. Unpublished site report, Caribbean Netherlands Science Institute, St. Eustatius.