History

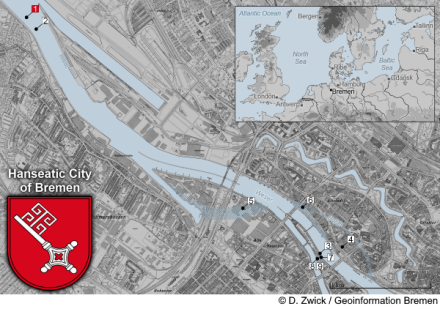

During dredging works in the River Weser as part of Bremen's port development, a hitherto unknown wreck was discovered on 8 October 1962, highlighted as No. 1 in the overview map below.

The historic significance of this wreck was immediately recognised by Dr. Siegfried Fliedner (Focke Museum), who identified the wreck as a cog (German: Kogge), one of the most prominent seagoing ships of the high medieval period and the Hanseatic League. No other wreck has been associated with a cog before, and this wreck became known as the Bremen Cog (German: Bremer Kogge) ever since. Despite this milestone event, a complete salvage of the wreck was by no means guaranteed at first. Only thanks to a concerted effort by the museum staff and committed citizens, who exercised maximum pressure on the political establishment, funding for the wreck was eventually provided after tough negotiations for a complete salvage operation, mostly carried out with a diving bell and helmet divers under the lead of Dr. Rosemarie Pohl-Weber (Focke Museum). The photos below show one of the rare events when the wreck was visible at an extremely low tide event.

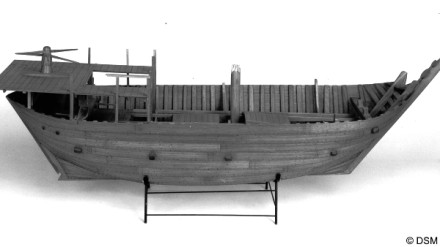

The necessity for an appropriate exhibition space also prompted the foundation of the German Maritime Museum (Deutsches Schifffahrtsmuseum; DSM) in Bremerhaven, in which a purpose-built exhibition space for the Bremen Cog was incorporated into the architectural plan. Even before the completion of the DSM building in 1975, the re-assembly of the salvaged ship-timbers started in November 1972. The wreck was completely reconstructed in 1979 and the waterlogged timbers were constantly sprayed with water throughout this period of time to prevent them from drying out. A water tank was constructed around the wreck, which was immersed in a PEG (polyethylene glycol) solution from 1980 to 2000 for long-term conservation.

Description

The Bremen Cog has never sailed, as it was swept away in an unfinished state from a shipyard in Bremen, from which it floated down the river and sank a few hundred metres later.

Based on Paul Heinsius' (1956) seminal work on Hanseatic ship types, Dr. Siegfried Fliedner recognised the striking similarity to what has been inferred as cog-type from iconographic sources, primarily the Stralsund seal of 1329 (pictured below), which was "reproduced from cogs" ("unser Stad Siegel ghenomed den kogghen") according to a contemporary written document.

The characteristics depicted on the seal were indeed also present in the Bremen Cog, and comprised the following features:

- a flat bottom with a sharp transition to the stem and sternposts

- straight up-raking stem- and sternposts

- a stern-rudder

- exceptionally high-sided hull

- clinker or lapstrake planking

- single square-sail

- fore- and aftercastles (crenellated)

Further constructional details were observed in the shipwreck itself and were later included in the extended definition criteria for the cog-type. These are:

- a keel-plank (instead of a proper keel)

- hooks that connected the plank-keel and the stem- and sternposts

- flush-laid (‘carvel’) bottom-planking gradually becoming lapstrake towards the hood-ends

- lapstrake side-planking

- the use of double-bend bent nails in plank-to-plank fastenings

- the use of moss as caulking material, held in the groove by laths stapled with caulking cramps (sintels)

In the following years, further wreck finds with similarities to the Bremen Cog from Denmark, Estonia, the Netherlands, Poland and Sweden have been also identified as cogs. Several of these associations have been called in question later, however, as these assumptions were based on the problematic premise that the Bremen Cog represented some kind of blueprint – or best example – of a cog (a concept alien to the medieval shipbuilder). The wreck was, perhaps inadvertently, perceived as such due to its great state of preservation and the fact that it was the first wreck to be identified as a cog.

This incongruence was first pointed out by Dr. Timm Weski, who noted that the cog type as defined by archaeologists was centred around constructional characteristics, indicative of a shipbuilding tradition rather than a type in the historic sense. The cog was mentioned in historic sources mostly as a large seagoing ship, but with no definite constructional criteria in the exclusive sense.

| Length | 76 ½ feet (23.3 m) |

|---|---|

| Beam | 25 feet (7.6 m) |

| Tonnage | 90 ton (45 last) |

| Displacement | 55 ton (28 last) |

Status

The Bremen Cog is exhibited in the German Maritime Museum in Bremerhaven. The PEG conservation was finalised in 2000 when the wreck first became visible to visitors. Initially, the exhibit was designed as a free-standing object by the insertion of a steel corset into the wreck's interior structure with a suspension system. This exhibition concept was dismissed a few years later, when deformations of the wreck's weakened timber structure became observable, which could not be compensated by the corset alone. Massive steel struts were set up to support the wreck also from the exterior side.

Several historically more or less accurate reconstructions of the Bremen Cog were built. The Kiel reconstruction is considered the most accurate one and sailing experiments have contributed much to our knowledge of the sailing qualities. Additional insights on the hydrostatic stability of the Bremen Cog were gained by computer-modelled test-runs.

Sailing cruises on cog reconstructions are offered for paying guests by various associations, like the Förderverein Historische Hansekogge Kiel e.V., through which the upkeep and maintenance costs are financed.

References

- DSM (German Maritime Museum).

Bremer Kogge (in German). - Förderverein Historische Hansekogge Kiel e.V.

Reconstruction of the Bremen Cog. - Baykowski, U. (1994).

The Kieler Hanse-cog. A replica of the Bremen cog.

Exeter: Oxbow. - Fliedner, S. (1964).

Der Fund einer Kogge bei Bremen im Oktober 1962.

Bremisches Jahrbuch, 49.

pp 8-10. - Hoffmann, G., Schnall, U. (2003).

Die Kogge: Sternstunde der deutschen Schiffsarchäologie.

Hamburg: Convent. - Hoffmann, P. (2001).

To be and to continue being a cog. The conservation of the Bremen Cog of 1380.

The International Journal for Nautical Archaeology, 30.

pp 129-140. - Lahn, W. (1992).

Die Kogge von Bremen (Band 1): Bauteile und Bauablauf / The Hanse Cog of Bremen (vol. 1): Structural Members and Construction Process.

Hamburg: Kabel. - Tanner, P., Belasus, M. (forthcoming).

The Bremen cog: reconstructed one more time.

In: Open Sea … Closed Sea. Local and inter-regional traditions in shipbuilding (= Proceedings of the 15th International Symposium on Boat & Ship Archaeology, Marseille 22-27 October 2018).

pp 313-322. - Weski, T. (1999).

The IJsselmeer type. Some thoughts on Hanseatic cogs.

The International Journal for Nautical Archaeology, 28.4.

pp 360-379. - Zwick, D. (2014).

Conceptual Evolution in Ancient Shipbuilding: An Attempt to Reinvigorate a Shunned Theoretical Framework (section: The cog delusion, pp. 61-65).

Southampton: Highfield Press.